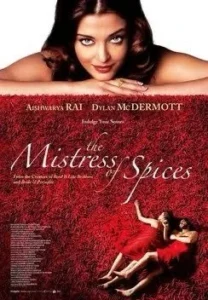

Book Review: The Mistress of Spices

The Mistress of Spices: Between Turmeric and Temptation

A review of Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s intoxicating novel that simmers with scent, sacrifice, and the surreal.

In The Mistress of Spices, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni brews a novel that is less read and more inhaled. It comes to you not in a rush of plot, but in curls of saffron-scented smoke, rising from the cauldron of memory and myth. Like Anita Desai’s women, the protagonist Tilo lives at the edge of silence. Like Lahiri’s characters, she carries the ache of elsewhere. And like Manu Pillai’s histories, the book understands power—its burden, its seduction, its price.

Tilo, born Nayan Tara in a faraway Indian village, is not merely an immigrant. She is an alchemist of grief. A Mistress of Spices. Her spice shop in Oakland is no ordinary place—it is a sanctuary of longing. Here, every jar whispers. Every cumin seed remembers. And every customer—lonely wives, angry sons, lost lovers—is more than they seem.

The Mistress of Spices follows a structure that mirrors its protagonist’s rhythm—measured, ceremonial, spiraling. Tilo is bound by sacred rules: never touch, never love, never leave the shop. But like all stories scented with forbidden longing, she eventually must choose between the world of duty and the world of desire. When an unnamed American enters her store, love arrives—awkwardly at first, then like a monsoon in the middle of California summer.

But it is not the romance that carries the novel. It is the quiet wars Tilo fights within. Between the girl she was and the goddess she was made into. Between healing others and discovering her own wounds.

The Mistress of Spices as a Lyrical Allegory

Divakaruni’s novel isn’t told in chapters. It is told in cardamom and cloves. In chili, which “burns to cleanse,” and fenugreek, which “remembers what the body has forgotten.” Each spice lends a mood, a meaning. Like a poet weaving verses into incense, Divakaruni turns the pantry into a pantheon.

The language dances—a sentence stops suddenly, then stretches like a sari in the wind. Some lines are short. Others carry the scent of long afternoons and unsaid things. Gary Provost would smile at this rhythm. It sings. It pauses. It weeps.

And yet, underneath the lush prose, there is bone. The bone of migration, of memory, of mothers left behind. “The Mistress of Spices” becomes less about the spices themselves and more about the spices we carry in our blood—the rituals, the resistances, the recipes for survival.

Tilo, the Reluctant Mystic

Tilo is one of those rare characters who feels like she has always existed—like the quiet woman you once passed in a spice shop, who met your eyes but said nothing. She is at once powerful and passive, mystical and mundane. A reluctant healer, a rule-bound rebel. Through her, Divakaruni speaks of the women who sacrifice their names at the altar of service, who choose silence over self, who turn their heartbreaks into healing for others.

Her lovers are less convincing. The American man—unnamed for much of the book—is a shadow in comparison to the glowing inner life of Tilo. Their chemistry is muted, as if the love story were a spice that lost its scent.

The Diaspora as Incantation

More than a novel, The Mistress of Spices is a diaspora diary disguised as a spellbook. Oakland becomes a map of fragmented homes: women afraid to speak English, cab drivers afraid to speak of love, children afraid to admit they don’t belong. In each customer who walks into the spice shop, we find the echoes of ancestors and the ache of assimilation.

Here, Divakaruni shines. With the tender observational eye of Jhumpa Lahiri and the sensory dexterity of Desai, she maps not just geography, but grief. The loneliness of the immigrant is not told. It is tasted.

The Failings of a Fable

But no spell is perfect. The novel, though rich in texture, sometimes falters in structure. The central romance, pivotal to the story’s arc, feels undercooked. The American man exists more as a device than a person, a foil rather than a flame. Some of the secondary characters—though vividly drawn—resolve their conflicts too conveniently, as if wrapped up in ribbons of resolution.

The magical realism too, occasionally teeters into the decorative. One wishes the spices did more than shimmer—they might have stirred plot instead of just atmosphere.

Why Read The Mistress of Spices?

Because it whispers to parts of you that are otherwise silent. Because it tells the story of women who heal others while forgetting how to be healed themselves. Because it understands that to migrate is to be both lost and found.

This is not a book for readers in a hurry. It is for those who like their sentences slow-cooked, their characters bittersweet, and their stories salted with metaphor.

The Mistress of Spices by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni is a lyrical tale of migration, magic, and identity. This review explores its themes, style, and cultural depth through a poetic lens.

Final Words

In the end, The Mistress of Spices is not a tale to be read, but steeped. Like the best of brews, it takes time. It leaves residue. And when you’ve finished, it stays on your tongue, fragrant and lingering—like the memory of a mother’s kitchen, or the scent of sandalwood on an old sari.

You do not read The Mistress of Spices.

You let it simmer inside you.