How Divakaruni unfurls a forgotten banner—and why its fabric feels startlingly like our own skin.

Dawn in a Room of Rusted Maps

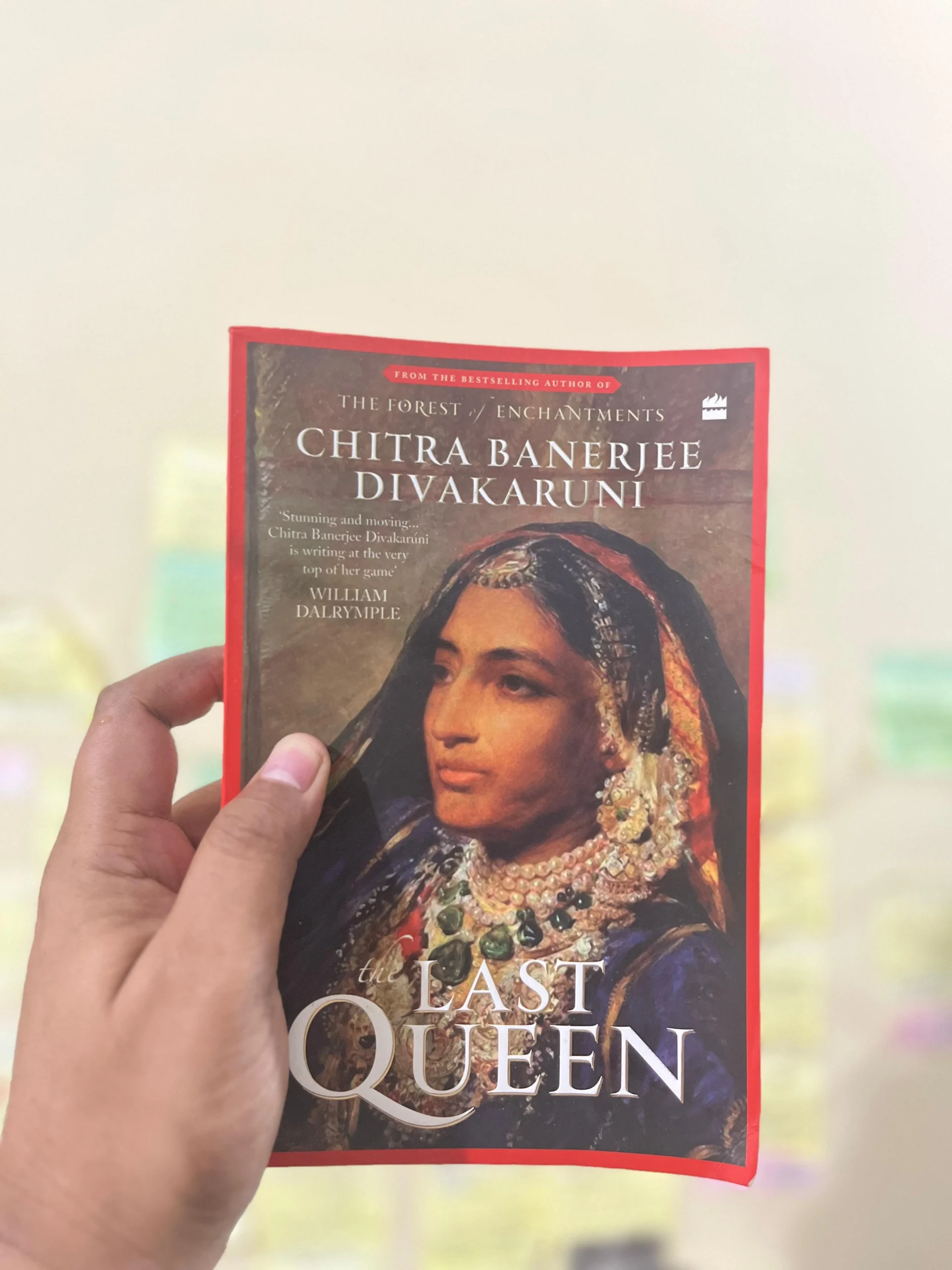

“The Last Queen review” must begin, I suppose, with a confession: I first met Rani Jindan Kaur not on a battlefield or a museum label but in a friend’s bookshelf, where my friend had taped her portrait above an economics timetable. The Maharani’s almond gaze watched us cram Philip Kotler and curse broken hearts. Years later, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s novel found me on a night train between Guwahati and Dibrugarh, and that gaze, a bit older now, almost wounded but returned.

What follows is not an autopsy of plot points. It is a walk along the fog-lit banks of the Ravi river, a rummaging through love-letters folded into state papers, a tasting of tear-salt on a treaty’s ink. It is personal because Jindan refuses to stay politely in the past. She flings her story, still warm, onto my keyboard and asks: And you? Whose empire do you obey?

1 The Veil That Became a Flag

Divakaruni opens with kennel-keeper dust and buffalo-milk lullabies, but soon the child with mud-braided plaits learns to wield language like a jewelled dagger. The Last Queen review would be meaningless if it did not dwell on that veil: not silk, not shyness, but strategy. When the new Maharani addresses the Lahore darbār unveiled, courtiers sputter, British officers smirk, and the empire’s marble trembles. A scrap of cloth turns manifesto.

2 Motherhood as Statecraft

Rani Jindan’s power is plaited into her son’s hair. Dalip Singh toddles through palace corridors while Anglo-Sikh conspiracies sharpen outside. Her lullabies are half-poem, half-policy memo. One cannot ignore how Divakaruni makes motherhood tactile: sticky mango pulp on miniature fingers, then sudden iron manacles on a child-king’s wrists.

3 The Anglo-Sikh Wars: Trumpets in a Closed Room

Historians detail troop numbers; Divakaruni gives us the clang of a cannon cooling at dusk, the brittle silence after surrender. Sikh generals argue over honour while East India Company clerks measure profit margins. In The Last Queen review we linger on one exchange: a British officer bows too low, smiles too wide. Jindan tastes the metal tang of betrayal before bullets fly.

4 Exile, or How Silence Learns to Sing

To imprison a queen is to slam a velvet-lined door on thunder, yet thunder leaks. From Chunar Fort to Kathmandu alleyways, Jindan stitches her memory into shawl borders, whispers passwords to loyal courtiers, plots—not revenge, but return. The Last Queen review pauses here, because exile is where Divakaruni’s prose unfurls like a monsoon cloud: sentences short, then long, then short again—Gary Provost’s rhythm pulling breath and heartbeat into sync.

5 Divakaruni’s Craft: When Research Starts to Breathe

A lesser novelist might drown in footnotes. Divakaruni composts them, grows blossoms. Archival decree becomes lullaby; treaty clause becomes choked sob. Through shifts in first-person narration, she invites the reader to taste jealousy, whip-sting, pomegranate sweetness. That intimacy explains why “historical fiction” feels too bloodless a shelf label. This is memoir written by a ghost who refuses to fade.

6 Punjab as Character, Not Canvas

Mustard fields humming like sitar strings, Lahore courtyards glowing with lamp-oil dusk, Sutlej waters carrying secrets downstream—place is pulse. The Last Queen review insists: you cannot understand Rani Jindan without tasting phulka smoke at dawn or smelling sandalwood on a dying king’s skin. Geography here is not décor; it is DNA.

7 Why the Rebel-Queen Still Murmurs in 2025

Borders redrawn, statues toppled, hashtags born and buried—yet Jindan’s question remains fresh: Who gets to remember, and who must beg for footnotes? When schoolbooks shrink women to sidebars, when policy meetings still seat patriarchy at the head, her veil-flag flutters above our timelines. The book therefore ends not with applause but a call: listen to the hush behind official history. It may be a woman, unmasked, rewriting the map.

Closing Paragraph: The Candle & the Mirror

When I shut the novel at 4 a.m., train wheels still clacking toward Dibrugarh, I felt the carriage tilt. Not physically, but in the intimate axis of memory: suddenly my grandmother’s stories of the 1962 border war, my own fear of boardroom glass ceilings, all aligned with Jindan’s thunder. That is the afterglow a great book leaves: you rise different, the room rearranged.

And so this write up bows to a woman who, stripped of court and child, kept her name warm enough to outlive marble. On a night when history felt too heavy, she granted me her veil, not to hide, but to wave at the oncoming dawn.

If you’ve read this far, I’m guessing the words found a home in your heart. Let me know what I thought by dropping a line in the comments and join the conversation. And if you’re still in the mood to wander, here’s another review of a book by the same author waiting just a click away –

https://psdverse.com/www-psdverse-com-the-mistress-of-spices-review/