Chronicles of a Matrilineal Kingdom’s Last, Long Echo..

There are books one reads, and there are books one walks into, like rain-soaked courtyards where memory clings to the squared stones.

It was not a railway waiting room that first introduced me to Manu S. Pillai. It was a room lined with books. A cup of over sweetened saah, the blue hush of an approaching evening, and False Allies lying on my lap like a secret whispered between two friends.

By the time I turned the last page, I knew that history was not merely the past, it was an old, breathing entity that could still lick the back of one’s neck.

That night, under the slack, unusually bright light of LED bulbs, I went looking for more.

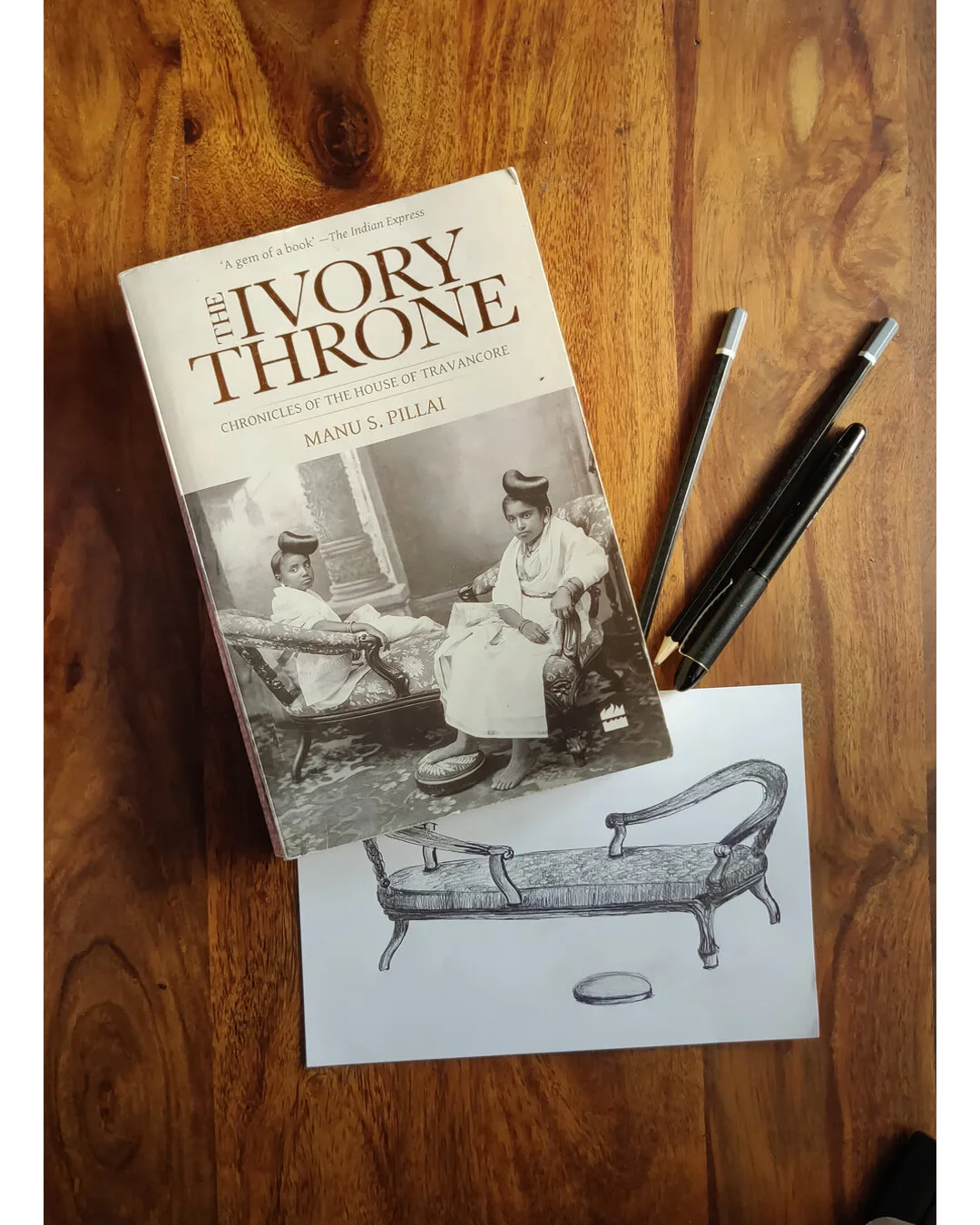

And what I found was The Ivory Throne, a book so vast, so shimmering with life, it did not feel written as much as summoned from the salt-smeared air of Kerala itself.

The Kingdom Where Power Wore Anklets

History, we are often told, belongs to men who sat astride horses and cut the air with their swords.

But Travancore was different.

Here, lineage loitered through the mothers.

A prince might be born with royal blood, but he was never king by his own right.

It was the women, the Maharanis who carried sovereignty in their wombs, passing it down not to sons, but to nephews.

Pillai’s first and most delicate achievement is this: he does not present matriliny as a quaint relic.

He lets it breathe, ache, evolve as a living, breathing system where gender roles tilted, twined, and sometimes trembled.

The Making of a Regent

At twenty-three, with the British breathing down the neck of every Indian throne, Sethu Lakshmi Bayi ascended.

Not to a throne, but to that more precarious thing, regency.

A world hemmed in by etiquette and English telegrams, by family jealousies and colonial suspicions.

Here, Pillai introduces her not with the drumbeat of conquest, but with the slow, trembling sigh of a woman forced into decisions whose consequences she can already foresee.

Lakshmi Bayi abolished the exploitative Devadasi system.

She opened school gates and hospital doors.

She walked the tightrope between tradition and revolution with a calmness that often felt, in the telling, almost mythic.

But Pillai’s great mercy is that he does not deify her.

Instead, he allows her to stumble, to yearn, to be lonely, a queen not of marble, but of skin and silence.

A Palace of Two Queens

If Sethu Lakshmi Bayi was the pulse of reform, her cousin Sethu Parvathi Bayi was its counterpoint, steely, ambitious, wounded.

Their rivalry, Pillai shows, was less a war than a slow corrosion, where letters carried hidden barbs, and every smile weighed more than a sword.

It is not easy, even across these lush pages, to choose sides.

Both women are products of a system that both imprisoned and exalted them.

Both loved and wounded in equal measure.

There are no heroines here, no villains.

Only people, flawed, frightened, sometimes ferociously brave trying to steer the tides of a world they did not make.

The Palace and the Jungle

But lushness can turn wild.

There are passages in this book long, aromatic, intricate that demand your absolute surrender.

Descriptions of gold-embroidered umbrellas, of tedious palace rituals, of minor family branches long since withered.

For the restless reader, it can feel like wandering through a jackfruit grove when one is thirsty for water.

Yet if you persist, the payoff is immense.

You will find yourself standing in the cool shadows of temples, your ears filled with the slow bell-tolls of a world slipping into twilight.

A Kingdom Remembered

Since its arrival, The Ivory Throne has become a quiet phenomenon.

It is whispered about in university halls.

It is argued over in drawing rooms filled with the smell of filter coffee and rain.

It is rediscovered by readers who realise that Kerala’s story is India’s story, and that the dance between power and tradition is an old, old thing.

A Goodbye

When I finally closed The Ivory Throne, I did not feel as if I had finished a book.

I felt as if I had shut an ancient door behind me. One that still sighed with the echo of bare feet on cool stone, the ting of anklets, the rustle of palm leaves against a monsoon sky.

Pillai, in his infinite tenderness, does not merely resurrect the past.

He shows us that it was never dead.

That it still lingers in language, in longing, in the shadows of forgotten courtyards.

And that, sometimes, the oldest stories are the ones we need most.

Quote

“Once I had a kingdom…”

The words fall into the silence like a broken conch shell.

A reminder that all kingdoms, like all memories, are ultimately stitched from longing.

Readings:

A Whisper from a Lost Throne

Perhaps every kingdom ever built was only a memory waiting to happen.

And perhaps history, when listened to closely enough, is not made of battles and dates,

but of barefoot queens walking across silent courtyards,

dreaming futures they would never live to see.

If so, then The Ivory Throne is not merely a book.

It is an inheritance, a slow, aching reminder that we are all, in the end,

keepers of broken crowns and forgotten songs.

The Fragile Geometry of Power

History does not survive because it was grand.

It survives because it was fragile.

A crown worn too tightly.

A letter left unread.

A whisper in a corridor that travelled across terrains for over decades, into a revolution.

The ivory throne was never made only of ivory.

It was stitched together from love and ambition,

betrayal and prayer,

hope and exhaustion.

To remember it is not just to study it.

It is to inherit its sadness, its wisdom, and its stubborn, irrepressible faith in the act of becoming.

All empires end, but memory endures like the smell of rain on the mud.