A River That Remembers: The Covenant of Water and the Mythic Pulse of Kerala

How Abraham Verghese looses a century of tides, surgeries, & sorrows—and asks whether story itself can be a lifeboat.

The Covenant of Water Begins in Stillness.

The Allepey backwaters wake early. In the first light, coconut fronds comb the wind, cinnamon smoke from a waterside hearth slips across mirror-smooth canals, and a lone cormorant perches, black silk on green glass, listening for the splash that will announce breakfast. In such hush you hear a softer sound: pages rustling like reeds.

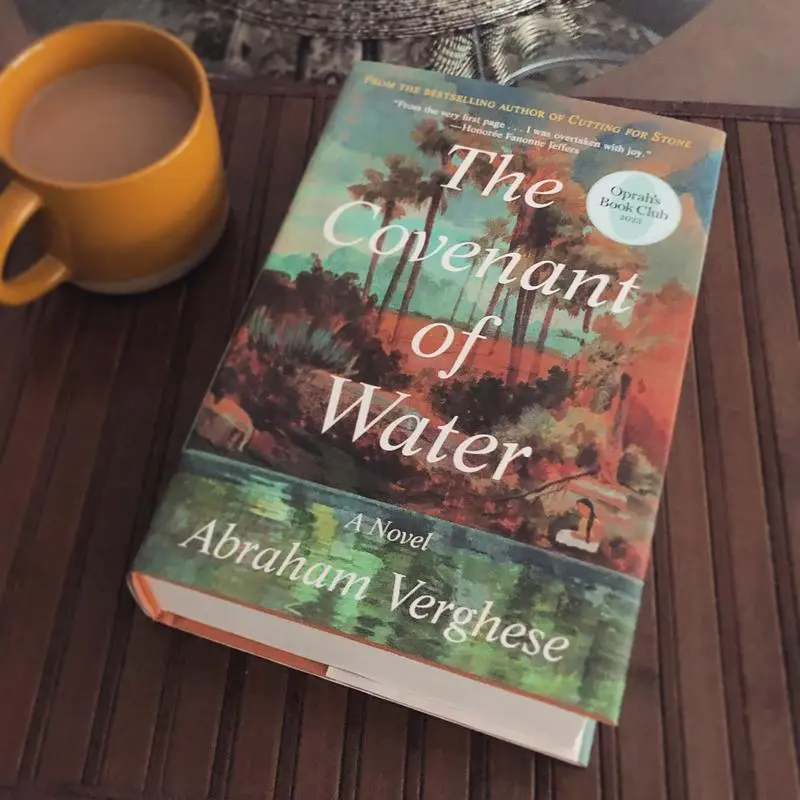

That susurrus is Abraham Verghese’s The Covenant of Water, a 736-page literary estuary where medicine meets myth and grief keeps time with the monsoon. Published in 2023, long-listed by Booker whisperers, crowned Oprah’s 101st pick, and camped on the New York Times bestseller list for thirty-seven weeks, the novel has already swollen into a cultural spring tide.

The Covenant of Water: A Matriarch’s First Step into Water

Verghese opens in 1900 with twelve-year-old Mariamma—soon to be Big Ammachi—sailing from her mother’s thatched childhood to wed a forty-year-old widower in Parambil, a fertile estate near Kerala’s coast. The bargain is ancient, the bride trembling, yet the river coaxes her forward.

From this single crossing grows a generational saga that unspools, braided and blue, until 1977. Each generation faces “The Condition”: at least one beloved is destined to drown. A local physician will later diagnose it as Von Recklinghausen disease, but long before Latin whispers arrive, the clan depends on omen, ritual, and a notebook called the Water Tree—where tiny drop sketches memorialize the drowned.

The Doctor-Novelist’s Anatomical Epic

If Cutting for Stone was a scalpel, The Covenant of Water is a full surgical theatre. In its sterile and sacred chambers, we meet:

- Digby Kilgour, a Catholic Scot barred from Glasgow’s medical guilds

- Rune Orqvist, the Swedish leprologist who saves Digby’s ruined hands

- Philipose, Ammachi’s dreamy writer-son

- Elsie, the painter who tries to outbrush grief

Verghese, still a practicing Stanford physician, threads clinical precision through every pulse. Sutures become metaphors; autopsies double as elegies. As NPR’s Jenny Bhatt notes, “he threads meaningful connections between macrocosm and microcosm so elegantly they are often barely noticeable.”

Yet this is no sterile ward. Verghese salts his sentences with Malayalam endearments, toddy’s sour tang, and elephantine secrets. Joan Frank of The Washington Post calls the result “a lavish smorgasbord of genealogy, medicine and love affairs” that floods the page like a kettuvalam barge rounding the bend.

The Covenant of Water as Fate and Forgiveness

In Kerala, everything arrives by water Portuguese spice ships, cholera spores, the telegram that announces independence, and sorrow thick as silt. Verghese leans into that elemental grammar.

Each chapter crests with a cyclone, ebbs with a drought, and paddles through canalbside whispers. The water metaphor never feels ornamental, it’s structural. The novel’s wet-blue spine. When characters refuse to bathe or tiptoe house-to-house on planks, readers clutch their breath. To avoid drowning, they must live half-drowned already.

Castes, Colonies, and the Quiet Politics of the Clinic

Verghese’s Kerala isn’t a postcard. It’s a palimpsest, scraped by caste, empire, and faith. The central Syrian Christian family negotiates privilege beside Pulayar workers tapping the same rubber trees.

Scottish Digby and Swedish Rune confront colonial arrogance and glass ceilings. They find liberation—and moral ambiguity—in India’s sweltering wards. The novel’s calendar includes:

- Socialism and land reform

- Famine

- The Emergency

Yet these are not historical bullet points—they’re barometric shifts in a single family’s weather.

The Covenant of Water and the Music of Sentences

Verghese’s prose, heavy with lineage and loss, could easily have drowned. But he let rhythm row the boat.

“Rain spent itself in silver needles. Then silence. Then, in a stillness broken only by a frog’s indignant cough, Big Ammachi felt the river change its mind and turn, ever so slightly, toward her.”

Yet in all this, Verghese remains unmistakably himself: part clinician, part lullaby-weaver.

Where the Embroidery Unravels.

Critics, not unlike monsoon clouds, gather in contradiction. Andrew Solomon in The New York Times calls the prose “softened curry” suggesting that Verghese sandpapers India’s grit. He questions the surplus of kindness: “So many good people. So many terrible things.”

Yes, coincidences abound. Resolutions float in on perfumed breezes. Dialogues shimmer a bit too self-aware. A tighter edit might’ve spared us some narrative eddies.

But there is counter-logic.

In a world addicted to quantifying loss, Verghese insists on the dignity of tenderness. His characters bleed, yes but they also pick up broken oars. Hope, he seems to say, is not saccharine. It is stubborn.

The Covenant of Water Beyond the Page

-

Oprah’s endorsement birthed a six-part podcast

-

Hollywood rights swirl in development tides

-

Libraries report heavy lending and feathered pages

-

Medical schools debate Digby’s ethical pivots

-

Indian households dissect Syrian Christian customs

The novel has slipped its moorings, irrigating unexpected lands.

Reading The Covenant of Water as Immersion Therapy

Halfway through, Philipose tells his mother:

“Fiction is the great lie that tells the truth about how the world lives.”

That line glimmers like a lanternfish beneath the tide.

Drowning is this family’s curse. But storytelling..oral, written, painted becomes a makeshift lifeboat. They catalog, mourn, and transmute loss into memory. They float each other forward.

Step Into the Backwater

The Covenant of Water is not a quick dip. It’s a pilgrimage canoe. Expect detours and eddies. But expect, too, empathy and awe.

Yes, it’s indulgent but so are:

- Kathakali performances

- Temple feasts

- The slow unfurling of water lilies

Verghese asks for your patience. And pays it back in texture.

If you loved the surgical adrenaline of Cutting for Stone, this is its delta: wider, deeper, slower.

If you’re new to Verghese, this is a novel as intimate as a diary, as sweeping as a census.

So pour yourself a brass tumbler of coconut water. Let the ceiling fan hum. Open to page one.

Somewhere, a cormorant lifts its wings.

Somewhere, a grandmother hums a boatman’s tune.

And somewhere, on your desk, lies a covenant—waiting to keep you afloat.