A Bookshop of Second Chances

Days at the Morisaki Bookshop and the Quiet Rebellion of Hope

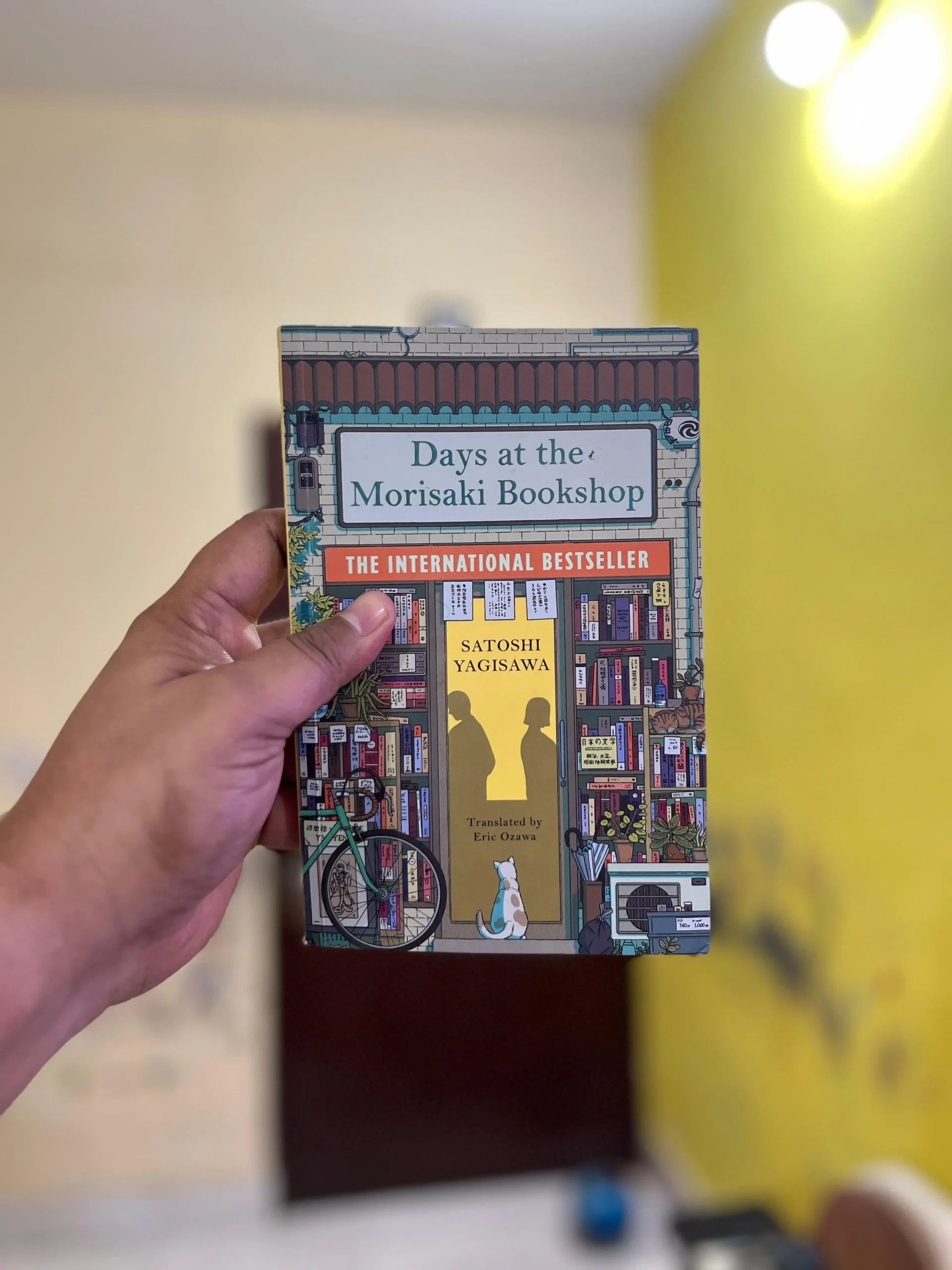

In the heart of Tokyo, where alleys coil like threads of forgotten stories, there stands a bookshop that smells of old paper and second chances.

It is cramped. Dusty. The kind of place where books lean on each other like tired pilgrims. The kind of place where you don’t just find novels, you find pieces of yourself.

Satoshi Yagisawa’s Days at the Morisaki Bookshop is a gentle hymn to such places and the quiet transformations they nourish.

It is not a novel that shouts. It whispers. It does not chase after high drama. It sits, cross-legged, in a patch of sunlight, asking you to sit with it awhile.

And if you do, it rewards you, not with fireworks in the tummy, but with something rarer: a story that feels like a hand reaching quietly for yours.

A Room Above the Shop

When we first meet Takako, she is adrift like a paper boat after the rain.

Heartbroken. Jobless. Hollowed by betrayal.

Life, for her, has become a narrow corridor of fluorescent lights and shallow breathing.

Then comes Uncle Satoru: eccentric, rumpled, owner of the Morisaki Bookshop and the unlikely ferryman who offers Takako a way across her sorrow.

“Come stay,” he says. “There’s a room upstairs.”

And so she does.

Not out of hope, hope has long since curled up inside her like a wounded thing, but out of exhaustion.

Above the shop, she moves into a small room smelling of yellowing pages and rain-soaked wood.

She wakes to the clatter of shutters, the rustle of customers, the low hum of a world that has kept turning, even as hers had stopped.

For the first time in what feels like forever, she breathes differently.

Outside, Jimbocho district stretches before her, a warren of bookshops, cafés, and alleyways heavy with the scent of brewing coffee and possibility.

The Alchemy of Paper and Time

At first, Takako is indifferent to the books that line the walls like sentinels.

They are old. Musty. Foreign.

She does not believe in magic anymore.

But slowly and this is the real magic, the books begin to seep into her.

Not with a shout, but with a whisper.

One afternoon, idly, she picks up a novel. Then another.

Each story leaves a small, almost imperceptible crack in the shell she has built around herself.

Reading, for Takako, becomes a form of silent rebellion.

A rebellion against numbness.

Against the easy narrative of defeat.

Through pages and paragraphs, she rediscovers curiosity. Wonder. Even laughter.

The bookshop, with its leaning towers of forgotten stories, becomes a kind of monastery where Takako slowly stitches herself back together.

The Bookshop as a Sanctuary

Morisaki Bookshop is not glamorous.

It does not gleam under Instagram filters.

It creaks. It leaks. It leans. It smells of mold and memory.

And yet, it is sacred.

Here, Uncle Satoru presides, not as a businessman, but as a quiet custodian of possibility.

He believes, almost stubbornly, in the privacy of his customers.

He sells them books, yes, but he also sells them something rarer: space.

Space to be lost. Space to be found. Space to be broken, or beginning again.

Jimbocho, almost a character here, is painted in loving detail, a neighborhood where even the lamplight seems to have softened with age.

A place where the past and present do not collide, but murmur to each other across narrow streets.

It is here, amidst this sanctuary of secondhand paper and secondhand dreams, that Takako begins to imagine a life beyond her grief.

The Return of Ghosts

Just as Takako is finding her footing, the past arrives, not hers, but Uncle Satoru’s.

His estranged wife, Momoko, appears one evening like a storm cloud gathering on the horizon.

Five years have passed since she left. Five years in which her absence became a silent tenant of the shop.

Her return brings tension, sudden, uncomfortable, like a draft through a half-closed window.

The story shifts.

The cozy rhythms of daily life give way to deeper, messier currents: forgiveness. Regret. The terrible, trembling courage it takes to begin again.

Some readers may find this pivot unsettling.

It fractures the warm cocoon the novel had so carefully woven.

But perhaps that is the point: healing is never linear.

It arrives, often, with old wounds reopening, and the wisdom to sit with the pain, instead of fleeing from it.

A Study in Smallness

Days at the Morisaki Bookshop is a small novel.

Not just in size, but in spirit.

It is about small moments:

- A cup of tea brewed too strong.

- A book chosen at random that feels written just for you.

- A shy smile exchanged between strangers across the counter.

It resists the grand, sweeping gestures so often demanded of novels.

Instead, it insists, tenderly, that smallness is not the opposite of significance.

Smallness, it says, is where the ‘sacred’ lives.

Characters Drawn in Watercolour

Takako is not a heroine who sets out to change the world.

She barely knows how to change herself.

And yet, in her hesitant steps, in her decision to stay, to read, to forgive, she becomes luminous.

A reminder that courage is often quieter than we think.

Satoru, too, is drawn with gentle strokes: a man clinging to his eccentricities as a shield against heartbreak.

His kindness is not loud, but steadfast.

A kindness that offers a room, a job, a place at the table, even when his own heart is cracked down the middle.

Secondary characters flutter in and out, like bookmarks briefly glimpsed between pages.

They are sketched lightly but fondly.

Wado, Takako’s new friend, adds a touch of humour and brightness, a fellow traveller in the search for something unnamed.

The Texture of Yagisawa’s Prose

Yagisawa’s language, is rendered with grace by the translator, is simple yet resonant.

There is an economy to his sentences, but also a deep well of emotion.

The descriptions are tactile: the smell of rain on pavement, the way old books creak when opened, the way grief sits heavy in the chest like unshed rain.

There is a particular beauty in how he captures stillness:

The still silence of a quiet afternoon.

The long, drowsy stretch of a Tokyo summer evening.

Reading Days at the Morisaki Bookshop feels like slipping into a warm bath at the end of a long day.

Comforting. Restorative. Unrushed.

The Gentle Rebellion of Hope

Ultimately, Days at the Morisaki Bookshop is not about grand reinventions.

It is about little salvations.

It asks:

What if healing looked like a dusty shop and a secondhand book?

What if hope wasn’t a sunrise but a match lit, flickering but stubborn, against the dark?

In Takako’s slow reawakening, in Satoru’s willingness to forgive, in every creaky, cluttered corner of the Morisaki Bookshop, the novel reminds us:

Second chances don’t always arrive with trumpets.

Sometimes they arrive as quietly as a page turning in an empty room.

And we lucky enough to be reading, are better for it.

“I realized how precious a chance I’d been given, to be part of that little place, where you can feel the quiet flow of time.”

In a world obsessed with speed, with noise, with endings shouted across rooftops, Days at the Morisaki Bookshop invites us to believe stubbornly, tenderly, in seemingly ordinary beginnings whispered from the back of a dusty bookshop.