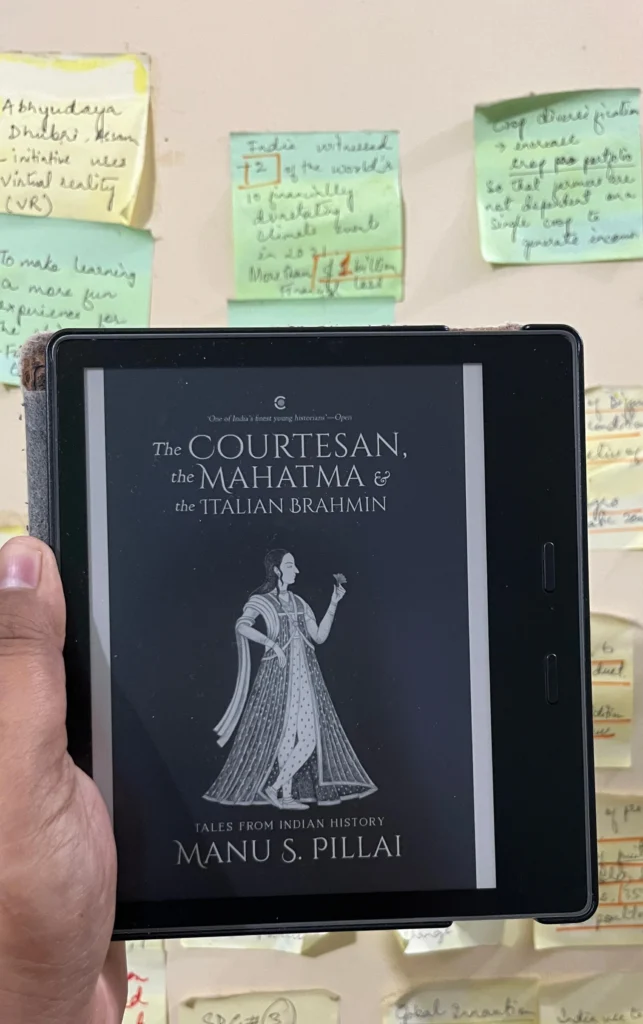

7 Reasons The Courtesan, the Mahatma and the Italian Brahmin Is the History Book India Deserves

The Courtesan, the Mahatma and the Italian Brahmin

1. The Courtesan, the Mahatma and the Italian Brahmin Begins with a Whisper, Not a War Cry

History, in most Indian classrooms, wears a grey Nehru coat and carries a pointer. It tells you what happened, when it happened, and who signed the Treaty.

But Manu S. Pillai lights a lamp instead. He opens a cedar-wood chest, and sixty-one essays tumble out, each shimmering with scent, scandal, and secret rebellion.

Dawn: Opening the Cedar Chest

History classes in India often smell of chalk dry, antiseptic, linear. Pillai prises open a cedar-scented chest instead. Sixty-one essays tumble out: a courtesan who became a warrior-queen; an Italian Jesuit who wrapped himself in Tamil and saffron; a Maratha prince who lampooned caste even as British canon thundered on the horizon. Each vignette is a bead; the silk thread that binds them is Pillai’s obsession with plurality. He does not build a single epic; he lays a banquet where Begum Samru clinks glasses with Roberto de Nobili, while Victoria Maharani, draped in imperial melancholy, watches from a polite distance. The result is less textbook, more travelling carnival, complete with mirrors that show us histories we never knew we inherited.

Inventory: Structure & Scope

The 400-page volume (Context, 2019; re-issued 2024) is split into two parts and an afterword. Part I rummages in the pre-colonial attic; Part II eavesdrops on the long, electric century that births the Republic. Pillai stitches columns first published in Mint Lounge into a seamless quilt, yet he adds fresh interludes and annotation. A thirty-page bibliography signals rigour, while endnotes retreat discreetly to the wings.

Voice: Silk Wrapped Round a Scalpel

Pillai’s prose wears a scholar’s monocle and a trickster’s grin. One sentence can pirouette through three metaphors, then halt at a punch-line aimed at modern chauvinists. When he describes Jahangir as “a man in whose veins flowed Persian, Turkic and Rajput blood—besides double-distilled spirits,” you hear Shashi Tharoor’s wit spliced with Dalrymple’s cinematography.

Gary Provost would applaud the rhythm: long sentences glide like the Yamuna under moonlight; short ones crack like temple bells. The reader never suffocates in dates. Instead, atmosphere does the heaviest lifting—rain glimmering on Travancore tiles, football boots thudding on Calcutta mud, gramophone horns blooming in a Delhi salon.

Themes: The Lateral Republic

- Plurality as Destiny. The book’s grand thesis is that India has always been an argument, never a monologue. Every essay—whether on Shivaji’s Persianate courtly rituals or the Muslim deity ensconced in a Hindu shrine—becomes a footnote to that thesis. Pillai’s concluding “Essay for Our Times” hammers the point: monochrome nationalism is ahistorical and, worse, unimaginative.

- Gendered Subversions. Pillai repeatedly hoists women onto centre-stage—Nangeli who sliced off her breasts in tax protest, Meerabai who refused to burn, the Gramophone Queen who sang herself into posterity. He shows agency where textbooks left voids, reminding us that patriarchy may silence, but it rarely erases.

- Caste & Counter-Caste. From Basava’s Lingayat revolt to the Phule duo’s war on Brahmin orthodoxy, social insurrections ripple beneath the regal tapestries. Pillai neither sermonises nor sanitises; he simply illuminates hypocrisy with anecdote and lets outrage grow in the reader’s rib-cage.

- Colonial Entanglements. The essays on Sir William Jones, Curzon and Victoria resist cartoon villains. Pillai concedes nuance: the Raj vandalised India, yes, but individual Britons sometimes preserved Sanskrit manuscripts or temple friezes. Complexity is not excuse; it is context.

Nuances & Juxtapositions

- Courtesan vs. Mahatma: The title’s triad itself is a study in contrast..eros, ethos, logos. By yoking them together, Pillai argues that civilisation is a crowded street, not a saint’s ashram.

- Peripheral Voices: An Assamese Naga patriot rubs shoulders with Travancore princesses, exploding the Delhi-centric lens. For a reader in Barpeta or Bangalore, the map suddenly looks more honest.

- Humour as Scalpel: Sarcasm slips in precisely where piety normally reigns. When Pillai describes a princely dinner where “the only vegetarian that night was irony,” the jest nicks deeper than a manifesto ever could.

Craft: Research Meets Storytelling

Behind the carnival flicker rigorous scaffolding. Pillai cites Portuguese archives for Jesuit sermons, Tamil palm-leaf manuscripts for Nangeli’s legend, and early photography for Begum Samru’s martial makeover. Yet the scholarship never curdles into jargon. The balance recalls Montaigne’s original essay: an attempt, intimate and exploratory, not a verdict chiselled in granite.

Critiques: Uneven Terrain & Column-itis

No feast is flawless. Some pieces especially the shorter columns feel like amuse-bouches when one craves a main course. A handful recycle anecdotes any history buff already knows (Lord Curzon again!). The geographical spread, though wider than Pillai’s Ivory Throne, still tilts toward the southern coast. Goodreads reviewers grumble about “information overload,” suggesting that dip-reading, not bingeing, suits the form.

Resonance in 2025

In an India where textbooks are either air-brushed or air-striked, Pillai’s mosaic feels insurgent. The book emerged in 2019, but the 2024 re-issue lands amid fresh controversies over syllabus pruning. Its insistence on shades of grey, on wayward queens and heterodox saints, becomes a political act.

Final Word: A Lantern for the Fog

Read The Courtesan, the Mahatma and the Italian Brahmin the way you would wander through Chandni Chowk: unhurried, curious, ready for paradox. You will bump into a Mughal painter who outlived three emperors, a Tamil Jesuit who out-Sanskritised Sanskritists, a courtesan whose sword glittered brighter than any dowry jewel. Some stalls will disappoint; others will intoxicate. But when you emerge, the fog of received wisdom will have thinned, and history will feel less like obituary, more like ongoing argument.

Pillai ends by pleading for an India that can hold multitudes and still hum a shared anthem. One closes the book hopeful that such an anthem exists—perhaps in a ragamalika where courtesan, Mahatma and Italian brahmin each supply a note, and the silence between those notes belongs to us all.

If you’ve read this far, I’m guessing the words found a home. Let me know—drop a line in the comments and join the conversation. And if you’re still in the mood to wander, here’s another review of a book by the same author waiting just a click away –

https://psdverse.com/review-of-false-allies-by-manu-s-pillai/

1 thought on “7 Reasons The Courtesan, the Mahatma and the Italian Brahmin by Manu S. Pillai Must Be Read in 2025”